Human Memory IV

3-4 Minute Read

Author: Bruce Morgenstern, MD

Purpose

Establish an understanding of the processes of memory and memory formation to assist in promoting student learning so that teaching faculty are better prepared.

Learning Objectives

Recognize that the key process for learning is retrieval of memories; and

Enumerate evidence-based processes to improve retrieval.

OK, if you read the learning objectives (and we will tell you why you should in a future faculty development piece), you will remember that we promised the same learning objectives in Human Memory III, and didn’t quite cover them. Here they are.

1. It’s almost self-evident that a memory that cannot be recalled is of no use, and in most respects is not a memory at all (forgetting is part of this). A plastic, growing, evolving neural circuit is all fine and good, but, somehow, we have to get back to that memory – those neurons, those neurotransmitters, those proteins.

Formally, this process is called retrieval. It can be intentional (let me see, what’s my mother’s maiden name?) or involuntary (tying a shoelace after having done it for years). The physiology and molecular biology of retrieval/recall are not as well worked out as for memory formation.

So, there are generally three steps in the process of long-term memory: 1) encoding the memory, 2) storing it, and 3) retrieving it. Retrieval is thought (not too much data to prove or disprove this concept) to involve two steps: search (my brain found a bunch of things regarding the Wizard of Oz) and recognition (my brain selected the “right” Wizard of Oz associated thing [by the way, who remembers that in one scene, the Scarecrow was holding a gun?(1).]

2. It’s generally accepted that retrieval/recall is dependent on a large number of factors, including things associated with the encoding of the memory (emotions, sleep, medications, for example, impact memory formation). Amongst the factors that can affect recall are:

Attention,

Motivation (shocking, these first two, we know),

Interference,

Context (what was I doing when I experienced X, what am I doing now that I’m trying to recall it),

State-dependence (I was taking an antihistamine when I studied, my recall is better if I am taking it when asked to recall),

Gender (women do better on delayed recall and recognition),

State of hunger,

Physical activity, and

Brain trauma (an obvious one, no?).

3. The brain is not a hard drive (or even a USB drive). Memories are proteins and neural circuits. The act of retrieval is an active reconstruction process, not a playback of a memory. Every time a memory is accessed for retrieval, that process modifies the memory itself; essentially re-encoding the memory. This explains the phenomenon of historical drift. Brancati discusses this phenomenon in a rather tongue-in-cheek paper: The Art of Pimping.(2)

Retrieval may lead to reconsolidation, as implied above. For factoids, retrieval practice (we’ll get to this in the next issue), is an evidence-based method to enhance memory. Retrieval practice is what should happen when we study, but it requires a deliberate effort.

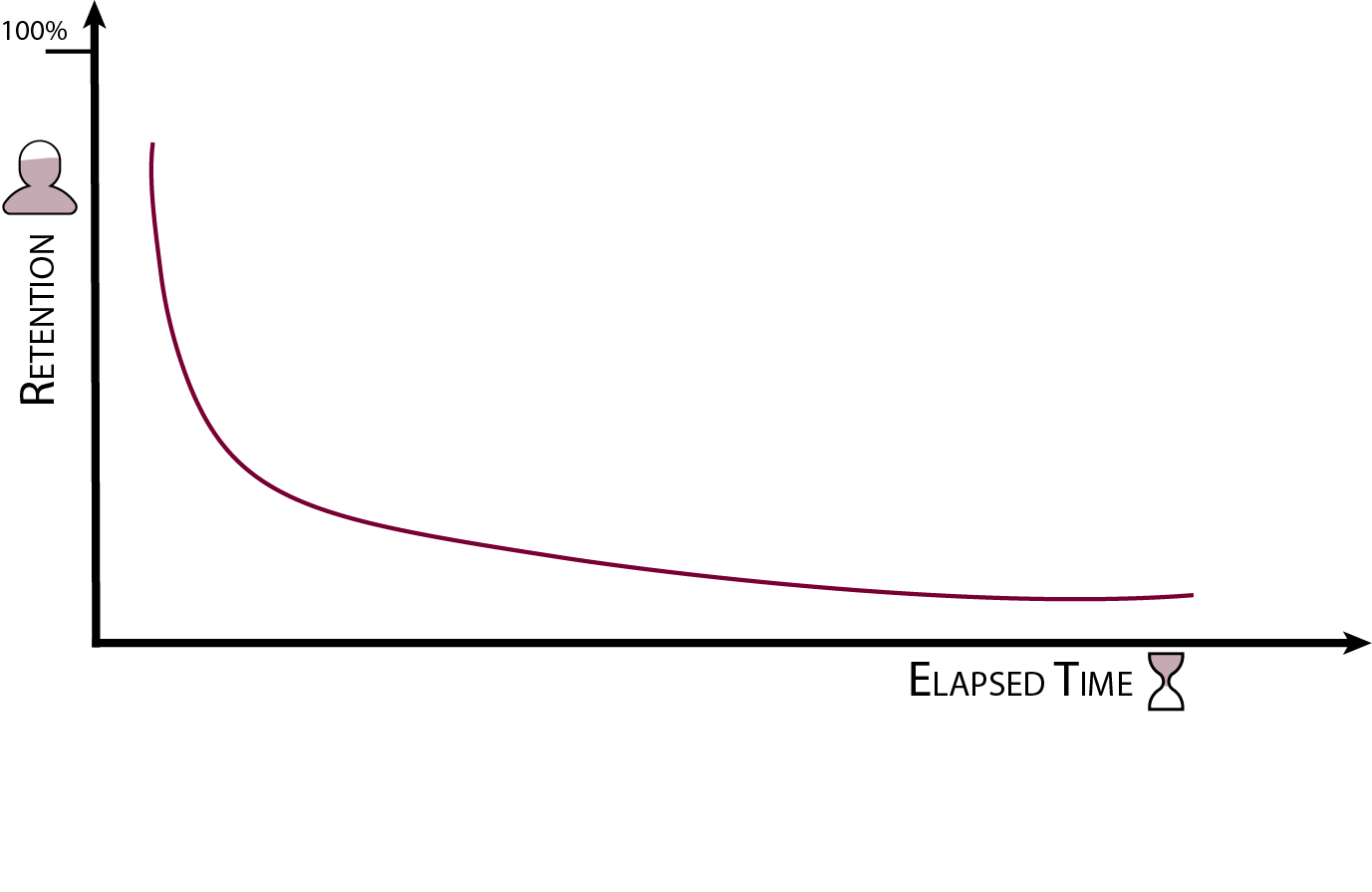

Let’s end on forgetting: Of course, there’s a forgetting curve – an effort to predict memory loss. It generally is depicted as this

If you must know, the curve is most closely fit by a power (exponential) curve equation. Forgetting is a totally normal phenomenon. Wait, what were we talking about?

Oh, yeah. You may remember (but we doubt that; why would you remember this?) in Human Memory III that we made mention of the fact that human memory may have deteriorated over the years (we wrote about this in the context of short-term, working memory, remembering 7 digits at a time and/or chunking). From the old TV show, the Colbert Report, there’s a great piece on the impact of the internet on memory.(3) That skit, in itself was based in part on Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu and Daniel Wegner’s paper in Science: Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at our Fingertips.(4)■

References

Vaughn. The Scarecrow Has a Gun. Debunkingmandelaeffects.com. Published October 13, 2016. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.debunkingmandelaeffects.com/the-scarecrow-has-a-gun/

Brancati F. The Art of Pimping. JAMA. 1989;262:89-90. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430010101039.

Colbert, S. Head in the Cloud. Comedy Central; 2011. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.cc.com/video/rtqznl/the-colbert-report-the-word-head-in-the-cloud

Sparrow B, Liu J, Wegner DM. Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips. Science. 2011;333(6043):776-778. doi:10.1126/science.1207745