Addressing Toxicity in Medical Education

5-6 Minute Read

Author: Becky Jayakumar, PharmD, BCIDP, BCPA

Purpose

To highlight the problem of toxicity in the clinical learning environment and describe one school’s mechanism for addressing it.

Learning Objective

1. Elucidate issues with toxic learning environments in medical education;

2. Discuss aspects of a healthy learning environment in relation to physical and psychological safety; and

3. Describe the functionality of a university committee to monitor professionalism in the learning environment.

Toxic Learning Environments in Medical Education

As a clinical pharmacist, I’ve witnessed numerous instances of toxicity in medical education from an attending berating a resident during rounds to the point of physically tearing up the resident’s note while calling it “bullshit” to a resident pulling a medical student aside to tell them they are “an idiot who shouldn’t be a doctor.” Colleagues tell stories too: the attending who said a female student needed “a hot beef injection” suggesting her attitude would be better if she “got laid”, the basic science lecturer telling female students not to go into urology because it is uncomfortable for male patients to have a female surgeon, and cliques and differential treatment on clerkships depending on the student’s career ambitions.

Medical education is infamous for its toxic learning environments—consider, for example, the abundance of tales of surgeons behaving badly while in the operating room,(1) and the fact that 40% of graduating medical students reported being publicly embarrassed and 21.5% being humiliated during their four years of medical school in the 2022 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire.(2) Additionally, these rates have been relatively constant over the past few years despite increased awareness of the problem.

Teaching Culture in American Medical Education

While ‘the learning environment’ encompasses all places where students learn including the clinic, the operating room, the simulation lab, the household (when providing household-centered care), the library, and university study spaces, toxicity and/or abusive behavior is often a learned behavior augmented by the hierarchy and power structure within the medical education system and is therefore often most pronounced in clinical education. Medical students who were mistreated often go on to become doctors who mistreat medical students leading to a perpetual cycle of abuse.(3-4)

The dominant teaching culture in clinical medical education, the Socratic method, can be inherently confrontational by challenging the knowledge and learning capabilities of students. Using this method faculty can easily transition from being instructive and useful to being verbally abusive or humiliating, especially when psychological safety in the learning environment has not been established.(5)

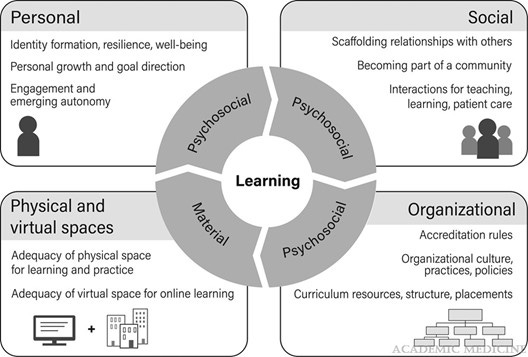

Physical Safety, Psychological Safety, and Healthy Learning Environments

The learning environment is comprised of a complex interaction of psycho-social-physical constructs, which is further described by the conceptual model of learning environments as depicted below.(6) The learning environment plays an important role in the student’s well-being, academic performance, and development of professional attributes and identity.(7-11) Some research shows medical students’ academic performance on the USMLE Step exam is better when they felt more positive about their learning environment.(8) The mental health and well-being of medical students are closely intertwined with their ability to learn.

Psychological safety, which is a “shared belief that the team, group, or environment is safe for interpersonal risk taking,(12) is increasingly recognized as an important precondition for learning. The principles of psychological safety have been related to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and a student can only move to address higher-level needs when their basic psychological and safety needs are fulfilled.(13) Developing and fostering a learning environment focused on psychological safety of the students has been shown to improve patient safety and innovation, which were positively related to knowledge sharing, team performance, quality improvement, and patient centered care. Additionally, when students felt psychologically safe, they were more likely to learn from their own failures and performance.(12) Similarly, a psychologically safe environment allows students to identify which skills they lack and wish to improve without judgment.(13)

In the wake of an endless stream of school shootings, the physical safety of students on school campuses is a concern nationwide, and the physical safety of students in hospitals should not be discounted as a potential impediment to learning. Hospitals often have signs throughout warning patients against aggressive behavior towards staff. Physical saftey is not limited to freedom from physical violence; another component of physical safety is talked about less—universal design. Recall the discussion of universal design in Core Aspects of Accessibility and its importance; namely, universal design ensures that all students have equitable access within the learning environment and the physical design supports learning. Attending to all aspects of the learning environment including the psychological, social, and physicial, is an important focus for medical schools.

LEAP Committee Overview

To meet the institutional challenges of providing a supportive learning environment and fostering professionalism, my current institution, Roseman University College of Medicine (RUCOM), developed the Learning Environment and Professionalism Committee (LEAP) based on the belief that all individuals at the college have a shared responsibility to foster a learning environment that is conducive to the ongoing development of explicit and appropriate professional behaviors for medical students, faculty, staff, and administrators. The LEAP Committee is a standing committee comprised of members from various diverse organizational aspects and is charged with ensuring that RUCOM maintains a high quality, professional, respectful, and nurturing learning environment. The committee will solicit data and feedback from a variety of sources including formal and informal feedback from students, clinical sites, student affairs, and the medical student promotion and review committee. Additionally, aggregate, de-identified learning environment and professionalism data from course and teaching reviews are forwarded to and reviewed by the LEAP committee. Based on the monitoring results, the LEAP committee formulates actionable recommendations for policy and procedure changes, faculty and staff development programming, and student wellness activities to the appropriate offices and the Dean’s Executive Committee. LEAP continuously monitors the implementation of its recommendations and assesses their impact on the learning environment. In this process of continuous quality improvement, the committee tracks progress and adjusts recommendations as needed to ensure sustained improvements.

Conclusion

Developing, fostering, and monitoring for a physically, socially, and psychologically safe and inclusive learning environment can help mitigate unnecessary stress in the inherently stressful endeavor of becoming a physician, and while all members of the academic medicine community are responsible for creating and maintaining a healthy learning environment, medical schools must also take responsiblity through organizational mechanisms like the LEAP committee. ■

References

(1) Jacobs GB, Wille RL. Consequences and potential problems of operating room outbursts and temper tantrums by surgeons. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3(Suppl 3):S167-S173. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.98577

(2) Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school graduation questionnaire: all schools summary report 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/62006/download Accessed April 10, 2024.

(3) Wiebe C. Medical Student “Hazing” is Unhealthy and Unproductive. Medscape General Medicine. 2007;9(2):60. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/557598. Accessed April 10, 2024.

(4) Hunt H, Barzansky B, Migdal M. When bad things happen in the learning environment. AMA J Ethics. 2009; 11(2):106-10.

(5) Major A. To bully and be bullied: Harassment and mistreatment in medical education. AMA J Ethics. 2014;16(3):155-160.

(6) Gruppen, Larry D.; Irby, David M.; Durning, Steven J.; Maggio, Lauren A. Conceptualizing Learning Environments in the Health Professions. Acad Med. 2019; 94(7):969-974.

(7) Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 149:334341.

(8) Wayne SJ, Fortner SA, Kitzes, JA, Timm C, Kalishman S. Cause or effect? The relationship between student perception of medical school learning environment and academic performance on USMLE step 1. Med Teach. 2013;35:376380.

(9) Christianson CE, McBride RB, Vari RC, Olson L, Wilson HD. From traditional to patient-centered learning: Curriculum change as an intervention for changing institutional culture and promoting professionalism in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2017;82:10791088.

(10) Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014; 89:14461451.

(11) Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: Integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87:11851190.

(12) Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Resrch. 2021; 21:773.

(13) Hardie P, O’Donovan R, Jarvis S, Redmond C. Key tips to providing a psychologically safe learning environment in the clinical setting. BMC Med Ed. 2022; 22:816.

(14) Thurber A, Bandy J. Creating accessible learning environments. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://citl.indiana.edu/teaching-resources/diversity-inclusion/accessible-classrooms/index.html