Author: Julpohng “JP” Vilai, MD, FAAP

Editors: Marin Gillis, PhD LPh & Judy Hanrahan, JD, MA

Purpose

To provide clinician educators how to use and reinforce shared decision-making strategies to teach medical students using vaccine hesitancy as a framework.

Learning Objective

1. Describe the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy through a shared decision-making framework;

2. Discuss common forms of shared decision-making between clinicians and patients; and

3. Discuss examples of shared decision-making discussions regarding vaccines.

As a pediatrician, I encounter vaccine hesitancy on an almost daily basis, yet medical school and residency did little to prepare me for having these uncomfortable conversations. At the beginning of my career, my approach towards patient adherence and the consent process was in line with a traditional paternalist model of medical decision making modelled by my attendings. But I was frustrated by this model because it rarely led to good outcomes. I tried another approach, one that was more of a negotiation, which did not yield very many more successful outcomes. The reality is that not everyone can be convinced.

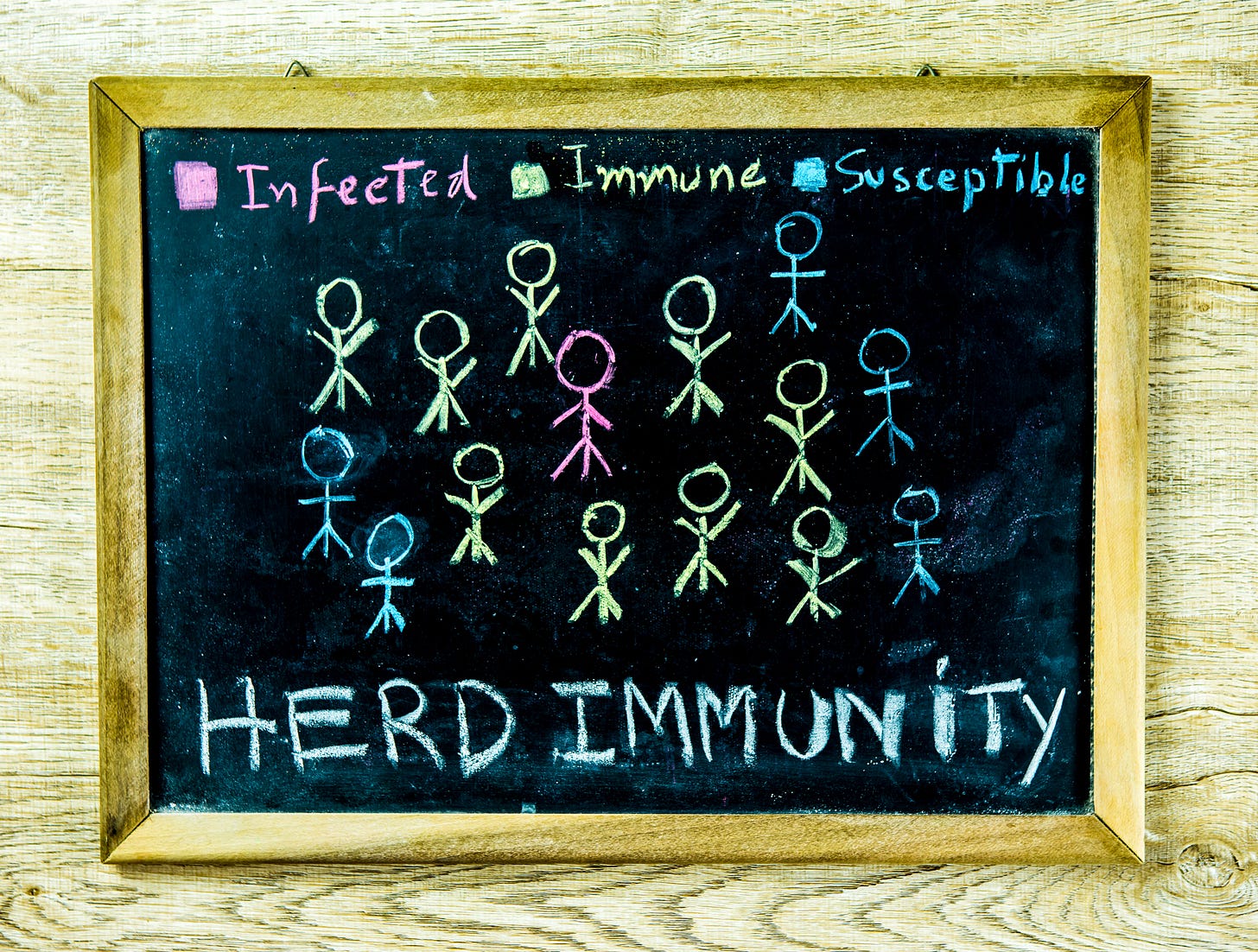

The good news is that herd immunity doesn’t require total assimilation, to borrow from Star Trek and the Borg. But the buffer isn’t huge. For example, polio requires ~80% of the population to be vaccinated, while the threshold for measles is ~95%.(1) So the question is, can we strike a balance between keeping potentially deadly outbreaks at bay while respecting individual and ethnocultural values?

Vaccine Hesitancy

Resistance and suspicion around vaccines is nothing new. When Edward Jenner developed smallpox vaccine in 1796, local clergy argued that mixing animal matter with human flesh was a direct violation of God’s will, while others expressed concerns that vaccines would cause “cow-mania,” developing bovine features as a result of vaccination.(2) The British Compulsory Vaccination Act of 1853 mandated smallpox vaccine for infants, sparking widespread rioting with opponents citing concerns about personal freedom and choice.(3) Sound familiar?

Anti-vaccination sentiment began to grow in the U.S. near the close of the 19th century as states attempted to enforce new vaccination laws.(4) In 2019, the World Health Organization declared vaccine hesitancy one of the top 10 global health threats.(5) In 2018, Betsch et al published a 5C’s model of vaccine hesitancy to describe and monitor the psychological antecedents of vaccination hesitancy or acceptance:(6)

5Cs: Psychological Antecedents of Vaccine Hesitancy or Acceptance

Complacency: Perceived low risk of acquiring vaccine preventable diseases, low in general knowledge and awareness

Confidence: Trust in vaccine safety and efficacy, health professionals, the system, and/or policy makers

Constraint: Structural and psychological factors

Calculation: Engagement in gathering information

Collective responsibility: Willingness to protect others

Vaccine hesitancy increased in response to the COVID-19 pandemic which introduced doubt in governments as well as health professionals and organizations, including the CDC.(7) To some extent, this heightened skepticism has generalized to erosion of confidence in other vaccines, particularly as misinformation is spread and endorsed by social media influencers, celebrities, and even practicing health care professionals.

Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy Through Shared Decision-Making

To continue with the Borg reference, resistance isn’t necessarily futile. Many patients and families often have important concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy and these actually present an opportunity to build confidence and trust. So, what can we do?

There are some conclusions I’ve drawn from my own practice over the years that have helped me navigate this space:

Attitudes toward vaccines seem to generally fall under 4 main archetypes: supporters, acceptors, fence-sitters, and refusers

Parents usually have their children’s best interests at heart

Clinicians and learners often lack adequate training to effectively address vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine supporters recognize the importance of immunization and offer little resistance to clinicians’ recommendations; acceptors generally go with the flow or may have some concerns but ultimately vaccinate; and refusers, including conspiracy theorists, are highly unlikely to be swayed from their positions. The bulk of my time is spent engaging the fence-sitters who are usually at least willing to listen and meet somewhere in the middle.

As a preceptor, I am frequently asked by learners to help them navigate vaccine hesitancy, but there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Even clinicians often report discomfort starting vaccine hesitancy conversations; many feel they lack the skills, knowledge, time, or motivation to have these discussions. Although I've yet to find an effective strategy for someone who thinks vaccines are a government effort to implant tracking microchips, clinicians can utilize, teach, and model certain shared decision-making strategies to improve vaccine hesitancy. Hargraves et al suggest that there are four distinct ways in which patients and clinicians can work together to address a patient’s concerns:(8)

1. Matching preferences

2. Reconciling conflicts

3. Problem-solving

4. Meaning making

Let’s illustrate these with practical examples.

Matching preferences

The problem is clearly defined and can often be established ahead of the conversation; its solution is in one of the options presented (i.e., vaccinate following the recommended schedule, not vaccinate at all, or vaccinate according to a modified schedule). Patients and families are often worried about making the wrong decision.

Example

Families may only want to give one shot at a time, do not want to use combination vaccines, wish to wait on some vaccines until the patient is older, or may desire to omit some products altogether.

Practice Tips

Address uncertainty by matching the threat of what could happen to the benefits, harms, and burdens that the patient prefers to take.

Be prepared to move quickly through your Kubler-Ross stages of grief to acceptance of a decision that may be different from your own preferences (e.g., from a public health perspective, even one vaccine is better than none).

Meeting families where they are will lead to enhanced trust in the clinician-patient relationship that can be leveraged to improve vaccine uptake down the road.

Reconciling conflicts

The problem involves an internal (tension between values or goals) or external (disagreements with others or the clinician) conflict. This requires reconciling conflicts within the patient or between parties so that an acceptable position is found.

Examples:

Some patients express religious concern that vaccines contain aborted fetal parts. While modern vaccines are still prepared from cells resulting from elective pregnancy terminations in the 1960s, they do not contain fetal cells. In fact, the Catholic Church supports the idea that “all clinically recommended vaccinations can be used with a clear conscience and that the use of such vaccines does not signify some sort of cooperation with voluntary abortion”.(9)

Caregivers or family members may disagree on immunization. If one parent is a supporter but the other is a refuser, for instance, the discussion can become complicated.

Practice Tips:

Know the evidence and use it judiciously.

Respect boundaries but recognize that the goal is to reach a mutually acceptable position.

Problem-solving

The problem is not clearly understood prior to the conversation but comes into sharper focus as it is used to find reasons to proceed in one way or another. This one is particularly tough because you may not know what the problem is until you are discussing it.

Example:

There is an assumption that families will vaccinate subsequent child because an older sibling was fully immunized. You may be blindsided upon mentioning vaccines then finding out that a family member experienced vaccine injury, online ‘research’ has found a link between vaccines and autism, or the ever-elusive ‘just decided to stop’.

Practice Tip:

Try to respectfully but firmly challenge incorrect beliefs with evidence.

Realize that the conversation may need to be revisited several times; this may allow you to gain the knowledge and resources you need to make a compelling argument.

Meaning making

The problem involves an existential threat or transition.

Example:

A classic example is HPV vaccine. Families often have the inaccurate belief that uptake of the vaccine is a green light for earlier sexual activity, or the association with sexual activity appears in conflict with the family’s values.

Practice Tips:

These situations will likely include bargaining; recognize that the patient or family will perceive a need to make personal sacrifices to accept the vaccine.

Emphasizing less controversial aspects (e.g., cancer prevention in this case) is often helpful; it allows families to weigh the strength of their beliefs against a desirable outcome.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality offers the SHARE approach, a 5-step model that can be useful for any form of shared decision-making:(10)

SHARE Approach

Clinician educators can consider these shared decision-making strategies with a broad range of difficult scenarios. Since we don’t usually like being told what to do, shared decision-making gives patients the respect, autonomy, and accountability to choose wisely. And while it’s rarely all or none, in many cases, something may be better than nothing.■

References

(1) WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Herd Immunity, Lockdowns and COVID-19. Accessed on June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19.

(2) Eisen EX. “The Mark of the Beast” Georgian Britain’s Anti-Vaxxer Movement. Accessed on June 25, 2024. Available at: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-mark-of-the-beast-georgian-britains-anti-vaxxer-movement.

(3) Durbach N. ‘They Might As Well Brand Us’: Working-Class Resistance to Compulsory Vaccination in Victorian England. Soc Hist Med. 2000;13:45-63.

(4) Prabhu M. The Long View: Ye Olde Anti-Vaxxers. Accessed on June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/long-view-ye-olde-anti-vaxxers.

(5) WHO Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Accessed on June 26, 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

(6) Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D et al. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0208601.

(7) WHO Report of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Accessed on June 26, 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf.

(8) Hargraves IG, Montori VM, Brito JP et al. Purposeful SDM: a problem-based approach to caring for patients with shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:1786-92.

(9) Pontifical Academy for Life. 2005. Moral reflections on vaccines prepared from cells derived from aborted human foetuses. Accessed on June 26, 2024. Available at: https://www.ncbcenter.org/files/1714/3101/2478/vaticanresponse.pdf.

(10) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The SHARE Approach: A Model for Shared Decisionmaking – Fact Sheet. Accessed on June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/tools/factsheet.html.