The Triangle Method for Clinical Teaching

7-8 Minute Read

Author: Julpohng Vilai, MD

Purpose

To familiarize clinicians with the Triangle Method for clinical teaching, a patient-inclusive technique, for the ambulatory care setting.

Learning Objectives

1 . Describe the Triangle Method and the roles of the learner, preceptor, and patient.

2. Discuss an example of how the Triangle Method can be utilized.

3. Discuss potential benefits and cautions regarding the Triangle Method.

I started my clinical teaching career at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital’s outpatient pediatrics clinic, where there was a lot of time to precept medical students and residents. I continued teaching when I entered private practice, but my technique evolved to accommodate the higher volume of patients, time-constraints of a busy practice, and often multiple learners at the same time.

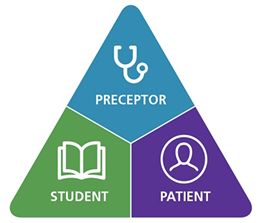

Outpatient precepting often follows a format where the learner sees the patient independently, privately presents to the preceptor, then the student and the preceptor return to the exam room. However, one small change to this practice can save time, and provide patients the, often welcome,(3,4) opportunity to more actively participate in the learner’s process—have the student present in front of the patient in the room. This method is known as the Triangle Method,(5) and it is a method I relied on heavily in my outpatient pediatrics practice. Some medical edcuators suggest that collectively including the preceptor, learner, and patient in management discussions is a best practice in ambulatory teaching.(3) This technique is akin to inpatient family-centered rounds, and evidence suggests that patients prefer to be included in plan discussions during bedside rounds.(1)

The Triangle Method

1. After seeing a patient independently, the learner presents to the preceptor in front of the patient.

2. The learner presents in standard sequence, using patient-accessible language rather than jargon. The patient corrects the history.

3. The preceptor helps the learner formulate a patient-accepted plan, teaching both the learner and patient.

We will illustrate this method with an example.

Lydia, a medical student rotating in a busy Internal Medicine clinic, is preparing to see Mr. Martinez a 44-year-old male with a concern of abdominal pain.

Step One: The Learner Sees the Patient Independently and Presents in Front of the Patient

Prior to the encounter, it is helpful to coach the learner and set expectations.

Preceptor: I’d like you to see Mr. Martinez. When you’re done, we’ll go back in together, you’ll present in the room, and we’ll develop a plan with the patient. When you present, let’s try to use lay terms the patient can understand. Does that sound okay?

Why: Setting the stage can help to alleviate any learner anxiety, clarifies the objectives of the encounter, and prompts the learner to anticipate the sequence and language required for the presentation. Similarly, it can also be helpful to brief the patient.

Preceptor: Hello, Mr. Martinez. I’m going to ask Lydia to summarize her conversation with you. If at any point you think something doesn’t sound right or is hard to understand, please feel free to interrupt and let us know right away. When she talks about what she found when examining you, I may double check a few things. I also think students can learn a lot from patients, so I might ask you to give Lydia some feedback later.

Why: Clearly communicating the sequence of events can help to eliminate confusion, tension, or discomfort. Introducing the idea that patients can be teachers encourages them to look critically at the interaction and prepares them for delivering meaningful feedback.

Step Two: The Learner Uses Standard Sequence and Patient-Accessible Language; The Patient Corrects the History

You ask Lydia to begin her presentation while ensuring you make eye contact with both the learner and patient. This validates that you are listening attentively, encourages the patient to interject if necessary, and values input from all participants. Observing the patient’s body language and facial expressions may also offer clues about when to ask for clarification.

Learner: Mr. Martinez is an otherwise healthy 44-year-old male presenting with a 3-day history of abdominal pain. He describes it as sharp and colicky, does not radiate, and he rates it a 9 out of 10.

Patient: Sorry, what does colicky and radiate mean?

Why: Correcting learner presentation errors as they occur correct avoids misleading the patient and provides the learner with immediate feedback (e.g., in this case, reminding the learner not to use medical jargon).

Preceptor: Thank you for asking. Sometimes we tend to use language that is too technical. I’d like to ask Lydia to start the presentation over using more common terms.

Learner: Mr. Martinez is a 44-year-old male coming in with 3 days of stomach pain. He says it is sharp but comes and goes. It doesn’t seem to move around to other areas and is about a 9 out of 10. His temperature is 100.3, blood pressure is 139/88, and heart rate is 102. On exam, he is in some distress and when I press on his stomach, he tenses up, it hurts worse when I let go, and the pain is the worst on the lower right side.

While Lydia describes her physical examination, the preceptor performs parts of the exam eliciting guarding, rebound, and point tenderness at McBurney point. The preceptor also checks for psoas and obturator signs.

Patient: Oh yeah, she also did that thing with my knees and hip, and it hurt like heck!

Why: Verifying relevant exam findings during the learner’s presentation saves valuable time (especially in a busy practice), models exam techniques for the learner, and may reassure the patient that the learner appropriately addressed the chief concern.

Preceptor: Thanks to you both. I’m sorry the exam was uncomfortable, Mr. Martinez. Is there anything else you would add?

Patient: Well, I forgot to mention the pain started near my belly button and moved to the right side. But, like I told her before, I’m not hungry which, if you look at me, is unusual and that worries me!

Why: As preceptors should feel comfortable interrupting and correcting, patients should likewise be given permission to verify the history or ask for clarification. Explicitly encouraging the patient to correct the history can allow for:

Clearer and more accurate history, particularly for more complicated or chronic complaints such as headache, abdominal pain, or mental health: Mr. Martinez clarified or added details that gave a more robust picture of his condition, and not relying solely on a learner’s memory or interpretation reduces the risk of recall errors

Addition of key facts: Mr. Martinez recalled that his pain began in the periumbilical region and radiated to the right lower quadrant, which he did not share with the learner initially

Clarification of details the patient considers important that the learner may inadvertently omit or misrepresent: Mr. Martinez described anorexia that Lydia forgot to mention

Validation: Had the patient not corroborated that Lydia did check for obturator and psoas signs, the preceptor might have assumed she had missed critical and pertinent exam findings

Step Three: The Preceptor Helps the Learner Formulate a Patient-Accepted Plan

At this point, you will ask the learner to generate a differential diagnosis, in order of importance.

Preceptor: I’m going to ask Lydia to tell me what she thinks is going on and we’ll come up with a plan together.

Learner: Inflammation or infection of the appendix is my top concern. It could also be a blockage of the bowel. Stomach flu is possible, but it seems less likely because of the specific findings on exam.

Why: Some learners will be more confident than others in developing their differential diagnosis. Using a method such as the One-Minute Preceptor can be helpful in guiding the learner toward a good differential with gentle redirection if needed. Approaches that can be useful include stage-whisper (“I’m going to quiz Lydia now.”) or couching the conversation (“Now we’re going to talk shop for a bit.”), especially if more in-depth discussion is required.

Preceptor: I agree. Appendicitis is at the top of my list too. Mr. Martinez, have you heard about appendicitis?

Patient: Yeah, my niece had to have surgery for that. Am I going to need surgery?

Preceptor: Well, we’re not sure right now. Surgery is not the only treatment, but I think the most important thing is to figure out if that is what’s going on. To do that, I think the easiest way is to send you to the Emergency Room where they can do testing and imaging to confirm. Then you’ll most likely see a surgeon who can talk to you more about options. Does that sound okay?

Patient: Not excited about going to the ER but, yeah, that sounds like a good plan.

Conclusion

There are several benefits for each participant in the Triangle Method.

Preceptor

Save time by not repeating parts of the history

Enjoy enrichment and variety

Describe enhanced professional status

Learner

Receive instant feedback

Appreciate patient’s confirmation of their interview findings

Feel more prepared for “family-centered rounds” on other rotations

Patient

Benefit from being included

Learn more about their personal health

Perceive more time spent with clinician

Report higher satisfaction

Although the Triangle Method has been utilized largely in outpatient settings, it can also be used in urgent care and the emergency department. Some clinical scenarios (e.g., patients with severe developmental/behavioral or intellectual disability, certain mental health conditions, or limited English proficiency) require the preceptor’s discretion and may be more conducive to precepting without the patient present. Additionally, while this method may be useful as an adjunct to traditional precepting, keep in mind that the need for direct observation of the learner’s examination skills as well as the preceptor’s feedback is still important and valuable. Irrespective of these circumstances, however, the Triangle Method can be a helpful, efficient, and effective technique for clinical teaching in the outpatient setting.■

References

1. Gonzalo J, Chuang C, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: An educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:792-8.

2. Rappaport D, Ketterer T, Nilforoshan V, Sharif I. Family-centered rounds: Views of families, nurses, trainees, and attending physicians. Clin Pediatr. 2012;51:260-6.

3. Pichlhofer O, Tonies H, Spiegel W, Wilhelm A, Maier M. Patient and preceptor attitudes towards teaching medical students in general practice. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:83.

4. Alguire P, DeWitt D, Pinsky L, Ferenchick G. Teaching in Your Office: A Guide to Instructing Medical Students and Residents. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: ACP Press; 2008.

5. Erlich D. Triangle Method: Teaching the Student in Front of the Patient. Acad Med. 2019;94:605.